The group of seven: from left to right – Matt, Me, Dave, Alan, Rich, Stuart and Paul. Photo: Matt Thompson

The water sparkled and danced in the shimmering light of the sun as I dipped my wooden paddle into its depths for the first time. A long-awaited dream of paddling in Canada, Algonquin Park no less was finally being realised as we pushed away from the wooden jetty to start our journey.

Meeting everyone the previous morning, some for the first time was less picturesque as we shook hands amongst a pile of duffel bags and rucksacks on a busy Toronto sidewalk (pavement to us Brits). There were seven of us in total – me, Stuart, Alan, Rich, Paul, Dave (and Matt who we’d meet up with later on). We would be spending the next 16 days with each other on a canoe trip with little to no contact with the outside world. I hoped we’d all get along.

We threw our packs into the hold and climbed aboard the Parkbus which would take us 150 miles northeast of Toronto to Algonquin Outfitters on Oxtongue Lake. There are various worries people have about travelling into the Canadian backcountry. Bears patiently waiting behind every tree to swipe your head off, getting zapped by lightning into a pile of dust, carelessly hacking your own fingers off with an axe or being crushed in the night by a remorseless tree limb. In spite of these eye watering hazards, our four hour bus ride was statistically the most dangerous part of the trip.

The coach pulled in to drop us off at the outfitters and I recognised it immediately having watched countless Kevin Callan videos on YouTube. We were greeted like old friends and made to feel very welcome. They gave us a quick tour and showed us our accommodation for the night where we met up with Matt, our seventh member and guide for the trip.

The storefront at Algonquin Outfitters next to Oxtongue Lake. Photo: James Werb

We spent the afternoon relaxing by the edge of the lake, occasionally peeling off to wander around the treasure trove of outdoor gear inside the outfitters and inevitably wandering back with a new item of clothing or camping gizmo that couldn’t be lived without. Most of which was then left behind when we realised how much portaging was involved and that the item in question was perhaps not quite as mission critical as first thought.

The sheer number of carbon and kevlar boats that adorned every rack surrounding the outfitters, including a whole range of shiny new Swift Canoes was a canoeists wet dream. I must have ambled around the Swift showroom, drooling and checking in disbelief at the weight of them at least three times.

The awesome lightweight display at the Swift Canoe ‘showroom’. Photo: James Werb

On & Off the Water

The following morning we regrouped in the outfitters for breakfast before getting stuck into the process of organising kit and food for the trip ahead.

The large tabletops in the backroom were covered with a huge variety of camping equipment from sleeping bags to toilet paper. We deliberated over the number of blue, plastic barrels we wanted to cram our mountain of food into before filling up our portage packs and trundling gear like a line of ants back to our tents to repack three or four times.

Before we loaded everything onto the trailer outside we picked out buoyancy aids and canoe paddles. I must have picked up about twenty different paddles, many of them more than once, to try and find the perfect companion. Realising that we probably did have to leave at some point I hurriedly made a decision and in retrospect almost certainly picked up the heaviest one I had laid hands on. A sort of cross between a cricket bat and pizza shovel. Still, at least I’d build up some muscle.

A collection of canoe paddles, some more refined than others. Photo: Matt Thompson

After piling in the minivan we set off off towards access point three and our start point at Hambone Lake. The roads got gradually narrower and as we approached and tarmac turned to dirt.

We wound between spruces and birches as Gord fought to keep the trailer from finding them around the tight turns. Just as it seemed that we had escaped civilization, much to our surprise we faced a large and fairly full car park sat seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

Too excited to care, with crystal waters sparkling just a hundred or so metres down the portage trail we unloaded everything onto the small wooden jetty. We said our final goodbyes to Gord, took some photos and climbed into the lightweight canoes for the first time.

Dipping our paddles in the water for the first time on a glorious, sunny day. Photo: James Werb

We paddled slowly across the lake, getting used to our new surroundings and paddling partners. Paul sat in the stern which allowed me to take photos and occasionally dip my paddle in the water. Our two entomologists, Dave and Stuart shared a prospector spending as much time with binoculars in their hands as canoe paddles. Alan, our resident lumberjack and Rich were the final tandem team, with Matt taking the solo Swift Shearwater.

Our first day on and off the water eased us gently into the trip. We soon reached the first portage, 295m into Ralph Bice Lake the yellow marker indicated. I quickly adopted the traditional canadian headwear and wandered down the path. Everyone heaved heavy, blue food barrels and sturdy portage packs onto their backs and headed off, resembling a string of ants marching through the woodlands. We had plenty of time to practice our portage skills over the weeks ahead as the distance markers increased and we spent equal time with the canoes above us as below.

The History of Algonquin Provincial Park

The area now designated as a provincial park was once inhabited by the Algonquin First Nations thousands of years prior to the European arrival. The word ‘Algonquin’ means ‘at the place of spearing fishes and eels’.

Unfortunately in spite of detailed instructions from a local fisherman back at the outfitters and Dave’s daily industrious efforts to secure a fish worth eating, we failed to live up to the Algonquin name during the trip. We didn’t waste the specially prepared ‘fish mix’ that we carried hopefully for most of the journey but I’ll get onto that later.

We didn’t catch an edible fish during the trip but is wasn’t due to lack of trying. Photo: James Werb

The park was officially established in 1893 as a sanctuary for wildlife. Located between Georgian Bay and the Ottawa River it is the oldest provincial park in Canada and covers an area of approximately 7,653 square kilometres (2,955 sq mi).

Logging activity (primarily for White Pine) shaped much of its more recent history and is still permitted and regulated within its boundaries. As we explored its lakes and shores we discovered traces of the early pioneering activity. Most notable was the ‘Alligator’ on Burntroot Lake. Sadly deteriorating near the shoreline but still in remarkable condition given that it was abandoned and left to rot.

The remains of an amphibious logging boat on Burntroot Lake called an ‘Alligator’ with the ability to cross land and water. Photo: Matt Thompson

The Alligator is an amphibious logging boat that was used up until the beginning of the 20th century. An amazing invention that allowed it to transport logs over water and between lakes by pulling itself over land using a huge winch. Over 200 were built and they were capable of travelling up to 2 ½ miles per day, even up steep inclines.

It was hard to comprehend the monumental effort it would have taken to haul thousands of logs over land even with the help of this wonderful machine. The side-mounted paddle wheels and powerful steam engine allowed it to travel over water in even the worst winds.

Before we left Burntroot Lake we paddled out to the appropriately named Anchor Island which is home to the anchor of the aforementioned boat. It’s now securely fixed with concrete after attempting a daring escape back in the summer of 2013. A group of campers attempted to take it home as a souvenir until they were caught by park rangers on White Trout Lake. To be honest I’m impressed they got it that far given the weight of it.

An ‘Alligator’ anchor which was nearly stolen in 2013. Most impressive is the fact they moved it so far before they were apprehended. Photo: James Werb

The booming lumber trade as well as the construction of the first railway in 1896 meant that railway workers, lumberjacks and their families took up residence within the park boundaries. The town of Mowat on the shore of Canoe Lake had grown to a population of over 500 by 1987.

On reaching Canoe Lake near the end of our trip we paddled under the old railway line and along the west shore where the town of Mowat once bustled with activity. Now completely overgrown, you’d be forgiven for not knowing that it ever existed as nature has reclaimed the land.

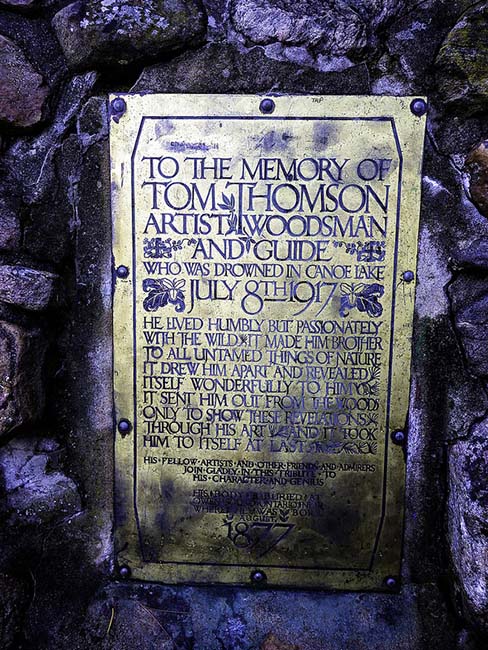

It would be impossible to talk about the history of Algonquin Park without mentioning Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. An influential artist, Tom Thomson travelled extensively throughout the park sketching and painting hundreds of scenes focusing on the natural, rugged scenery of the Ontario landscape.

The scenery was wonderful and must have provided endless inspiration for those artists. Photo: James Werb

The Group of Seven was a collection of painters who were directly influenced by Thomson’s work and captured the beauty of the landscape in much the same way. He died before its formation but it’s impossible to talk about one without the other as he was instrumental in influencing its inception.

The memorial plaque to Tom Thomson on Canoe Lake. Photo: Matt Thompson

Their works of art are now famous around the world though Thomson’s death is still shrouded in mystery. He died on Canoe Lake on 8th July 1917, the official cause of death cited as drowning. In spite of this there are many theories surrounding his cause of death including suicide and murder.

Now there is a cairn and totem pole erected on Canoe Lake to commemorate his life.

Field Repairs

We’d no sooner set off after lunch on the first day when Matt informed us that his seat had snapped. We headed back into shore to make a repair using a small branch and a lot of paracord. Paul had a similar problem with his stern seat later on in the trip and once repaired we swapped canoes with one of the other pairs.

Unfortunately for me Paul hadn’t yet quenched his thirst for canoe seat destruction as one evening he shouted back to me from shore that mine was now snapped as well. Between us we fashioned yet another repair using a length of Alder branch as a splint and again bound it with some paracord. I’m not sure if three broken seats on a canoe trip is a record but it’s definitely up there. It also wasn’t the only things to break.

A particularly windy evening did some lasting damage to our group tarp though fortunately it was still serviceable. More amusingly (though perhaps not for Matt) was his rude awakening one night as he crashed to the floor when his hammock gave way.

The lesson to be learned is things can and will go wrong on a trip at some point and you have to be able to adapt. Having a lot of paracord and a few simple tools meant that we were able to carry on and mend most items. In fact when we got back the staff at the outfitters commented on the quality of our bodging skills.

Food

Algonquin Outfitters did an amazing job of providing us with a varied diet considering the number of us and the length of the trip. It was the area that caused them the most anxiety to get right and for good reason.

Food takes on a whole new importance when you’re out in the wilderness for an extended period of time. It affects your mood and obviously needs to give you the required energy for the day. Certainly as the trip went on our conversations regularly gravitated towards food related subjects.

The first few days we had fresh food like peppers, mushrooms and oranges. After that the number of fresh items decreased and we ate mainly freeze-dried backcountry meals out of a packet.

Dave sampling the delights of ‘fish mix’ bannock. Certainly an acquired taste. Photo: James Werb

It has to be said that some of these were more successful than others and everyone had different preferences. One notable concoction was Huevos Rancheros, a sort of Mexican breakfast. I say ‘sort of’ because it had the consistency of vomit and as far as I was concerned the flavour of it as well. Matt has assured me that it is a food though I’m yet to be convinced.

The fish mix that I mentioned earlier unfortunately wasn’t used with any freshly caught fish but instead Matt made a makeshift bannock from it. It had an unusual flavour with a hint of lemon and suffered mixed reviews.

Food becomes very important on a trip, especially when you are burning through a lot of calories. Photo: James Werb

That aside, the majority of meals were edible and many even enjoyable. It was the quantity that was lacking on a number of occasions especially after have been portaging for a number of hours during the day.

Waist sizes were regularly measured and there was even delight by some members of the group as they tightened their belts one more notch. Not wanting to lose weight, at meal times I felt like a cross between a hyena stalking a carcass and Stig of the Dump as I polished off any leftovers. Even so I still lost half a stone.

The other consideration is storing and preparing food so as to not attract any unwanted visitors in camp. In the UK probably the biggest threat for a canoeist is the predatory swan claiming hapless victims as they gently paddle down the local canal. Well that and of course the infamous Scottish Haggis. In Algonquin they have a lot of bears and though attacks on people are extremely rare they regularly raid campsites looking for food. It’s important therefore to take precautions to protect your food and most importantly the bear.

We always made sure to wash our dishes away from camp and stored our food in barrels which were hoisted up into the trees. Not only food but also toiletries and toothpaste as Mr bear can’t tell the difference. Hanging the food was a daily ritual.

Usually a couple of us would head back into the woods away from our campsite while it was still light to find a suitable tree and set about throwing ropes over limbs strong enough to support the weight of the barrels. That almost always meant more than one tree as we had quite a few barrels to lift up. It was also important to be able to find the tree again after it got dark (on one occasion it took me 15 minutes to find it again).

It’s important to hang your food in bear country as much to protect the bear as yourself. Photo: James Werb

After eating we packed everything into the barrels and heaved them into the trees. They had to be high enough off the floor to stop a bear reaching up to get them and far enough away from the trunk so they couldn’t climb and get them. Not as easy as it sounds.

Any leftover food (and there wasn’t much) was usually thrown into the fire. It was by doing this that we also discovered the almost indestructible properties of Canadian cheese. We had a block left over and it was looking a little worse for wear by the latter stages of the trip so one evening we threw it into the camp fire. As it turned out probably not the best plan.

The few of us who were still awake went back into the woods to hoist the remaining food barrel and noticed the very distinct aroma of burnt cheese wafting rapidly through the trees. We feared that any bear within a 10 mile radius and not suffering from a blocked nose would be immediately attracted to our campsite. We hurried back to stoke the fire and hopefully destroy the evidence but there seemed no hope of getting rid of it. It just wouldn’t die.

I’m not sure whether we were suffering from the dramatic effects of cheese inhalation or fear of an imminent bear attack but we found the whole situation very amusing and soon fell about laughing. Fortunately after frantic attempts to break it up with sticks and increasing the temperature to unhealthy levels the cheese did eventually disappear and we weren’t all mauled in our tents that night.

Wildlife

After Matt mended his canoe set on the first day we were rewarded with a greeting by a group of very friendly Loons. Somewhat of a rarity in the UK but these guys were quite happy for us to paddle right up next to them as they occasionally bobbed under the water and reappeared elsewhere.

There was at least one pair of loons on every lake. Their ghostly call is iconic. Photo: James Werb

There was rarely a day on the trip when we didn’t see or hear them. It was wonderful to listen to their ghostly calls in the morning or evening around camp, or at least most of us thought so. Paul was less enamoured by their presence after the first couple of days as they routinely acted as his alarm clock. A call of a loon was often followed by Paul replying “noisy little shits!”

Aside from black bears the other iconic mammals of Algonquin Park are moose and wolves. We never saw or heard either though we found some hoof prints of a moose in the sand near one of our campsites.

Fortunately for us there weren’t many insects while we were there, which was one of the reasons we chose to visit in September. Earlier in the year insects such as black flies, deer flies and mosquitos are a notorious hazard. There were some mosquitos around while we were there but very few luckily, as it turns out I am quite susceptible to their bite. I was the only member of the group to be bothered by them and they attacked me at any available opportunity.

There were quite a few days when I was nursing a very swollen finger or unable to remove my watch as my wrist doubled in size. As I ran my hand over the back of my neck it felt like a mountain range where I had been the victim of a number of airborne assaults.

A wasp sting finished off the collection as I walked down one of the portage trails. An intense burning sensation struck my hand as I launched Paul’s water bottle into the air in shock. It’s fair to say that the insects were not my friends.

We passed numerous beaver lodges and dragged or furiously launched our canoes over some well constructed dams. Notably, on the third day we tried to reduce the length of a portage by ignoring the sign and continuing downstream. The water levels were low due to a very hot summer and a beaver dam stretched out across the width of the river.

Hauling canoes over a well built beaver dam. Photo: James Werb

Matt eased over it straightforwardly but the rest of us in tandem canoes carrying more weight had a less delicate approach. Paul and I headed full speed towards the edge of the dam and as we crested over the edge the canoe paused and seesawed over the woody ledge. After getting out we heaved the canoe down into the lily-strewn waters below.

In spite of the obvious presence of these wonderful rodents they were not easy to spot. Matt caught a glimpse of one near the dam but I was the only one to get a really good look near one of our campsites. There was a long headland and an impressive beaver lodge constructed right on the tip. Dave, Stuart and I went to investigate it one evening and we could hear something sploshing around in the water below.

A reasonably large tree had been felled nearby by this impressive creature so it seemed like we were in luck and the lodge was active. I walked back to the lodge early the next morning, just before sunrise to see if I could catch a glimpse. The sun hadn’t quite risen over the conifers as I heard a thump and a splash as the water rippled in front of me.

A wonderful experience watching this beaver swim in front of me as the sun rose. Photo: James Werb

There it was, a magnificent beaver swimming around in the lake not far from shore. It thumped the water again with his tail and disappeared under the surface, probably warning of my presence. I stood still in the cold morning air watching for about 5 minutes as it swam backwards and forwards through the calm water. It was a wonderful experience and a perfect start to the day.

A magnificent Bald Eagle surveying it’s surroundings. Photo: James Werb

We were also treated to some otters playing in the lilypads at Hailstorm Creek nature reserve very close to our canoes and glimpsed a couple of bald eagles usually perched in the tallest trees surveying the area. Algonquin Park is host to some incredible wildlife and journeying by canoe is one of the best ways of getting close to it.

Camps

Campsites in Algonquin Park are all well marked with orange signs. Bear in mind that if you’re thinking of visiting the park that you need to reserve your campgrounds in advance. Your route must be approved by the park rangers and you’ll need to let them know which lake or river you will be staying on each night.

Campsites in Algonquin Park are well marked but need to be reserved in advance. Photo: James Werb

This system means that you’ll be guaranteed a campsite each evening though you may not get your first choice depending on how busy it is. We found that the nearer to the access points you are the more likely it is that at least some of the campsites will be occupied.

All of the campgrounds that we stayed at had a fire pit and a long drop toilet somewhere in the woods nearby. We never had a bad site and most had wonderful views. My favourites were camped by a river, waking up to the sound of cascading water as the morning mist was gently carried downstream.

I expect that earlier in the year these sites would be quite buggy and far less enjoyable as a result. We had one occasion where the mosquitoes were a pain but sitting near the smoke of the fire helped. Matt took his sleeping gear onto an exposed rocky outcrop that enjoyed a bit of a breeze to keep the insects at bay.

Portaging

Portaging can be the bane of many a canoe trip and Algonquin Park is famous for having some notoriously challenging ones. The Dickson-Bonfield is perhaps the most infamous at nearly 5.5km long. The longest single portage we faced was the 3.75km route from Hogan Lake to Big Crow. Bear in mind as well that unless you’re packing very light that you’ll have to cover the distance at least twice and sometimes three times depending on your strategy.

According to Bill Mason “anyone who tells you portaging is fun is either a liar or crazy”. I fall into the latter group. Photo: James Werb

I’m probably slightly abnormal when it comes to portaging as I actually quite enjoy them. Don’t get me wrong, hauling heavy packs and canoes over a few miles at a time isn’t always pleasurable but I do enjoy the physical challenge. On some days we were paddling long distances and the portages were a welcome relief as a chance to stretch our legs and enjoy the change of scenery underneath the forest canopy.

Rapids

While there are white water opportunities in the park our route was generally flat paddling. It had been an exceptionally hot summer so water levels were fairly low by September. Most rapids we encountered were very small and often not runnable in a canoe so we either lined our boats down or hit the portage trails that were always available to skip the moving water sections.

In some areas dams and waterfalls made portaging a necessity but our last couple of days offered an opportunity for some more exciting sections as we navigated down the Oxtongue River and back to the outfitters.

Lining down some rocky shallows. Photo: James Werb

For many including a number of our group these rapids were straightforward. Stuart did incredibly well considering he wasn’t a canoeist and I have to admit I’m not the most competent on moving water so some of the sections were a little bottom-clenching but most definitely fun. Fortunately I had Paul in the stern shouting instructions and we made it down the Oxtongue unscathed and dry.

Lining and wading were other methods we used on a few occasions to avoid portaging. Mostly this was straightforward enough and went without incident.

On one occasion Dave had a slight mishap with a rather greedy rapid. The line was a bit short and the recirculating water took hold of the canoe and sucked it into the flow. As the water poured in over the gunnels, and amidst a range of shouted instructions from the shore, Stuart could only look on helplessly as his and Dave’s kit started floating down the river.

Al and Rich were on hand to pick up their gear before it travelled downstream any further. The canoe was heaved to the shore and emptied, and the whole event provided us with some great entertainment for the start of the final day.

The Journey in Figures

Here were the approximate distances that we covered by day:

| Date | Day | Distance Paddled (mi) | Distance Paddled (km) | Distance Portaged (m) | Distance Portaged (m) x3 |

| 4th Sept 16 | 1 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 730 | 2,190 |

| 5th Sept 16 | 2 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 730 | 2,190 |

| 6th Sept 16 | 3 | 9.9 | 15.9 | 1,030 | 3,090 |

| 7th Sept 16 | 4 | 10.7 | 17.3 | 375 | 1,125 |

| 8th Sept 16 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9th Sept 16 | 6 | 9.6 | 15.4 | 535 | 1,605 |

| 10th Sept 16 | 7 | 3 | 4.8 | 790 | 2,370 |

| 11th Sept 16 | 8 | 5.7 | 9.2 | 3,700 | 11,100 |

| 12th Sept 16 | 9 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 3,750 | 11,250 |

| 13th Sept 16 | 10 | 9.1 | 14.6 | 1,395 | 4,185 |

| 14th Sept 16 | 11 | 8.6 | 13.9 | 2,235 | 6,705 |

| 15th Sept 16 | 12 | 3.7 | 5.9 | 3,325 | 9,975 |

| 16th Sept 16 | 13 | 6 | 9.6 | 790 | 2,370 |

| 17th Sept 16 | 14 | 5.5 | 8.9 | 635 | 1,905 |

| 18th Sept 16 | 15 | 16.5 | 26.5 | 440 | 1,320 |

| 19th Sept 16 | 16 | 13.4 | 21.6 | 1,645 | 4,935 |

| TOTAL | 113.4 | 182.3 | 18.78km | 56.34km |

Video

Here’s a short 5 minute video of our journey. Hopefully you’ll forgive my rather amateur editing skills as it’s the first one I’ve attempted.

Photos

Here are my photos from the trip:

Here are Matt’s photos from the trip:

Share this Post

8 Comments on “Group of Seven: Canoeing Through Algonquin Park”

Great reading your blog of the trip! I found it following a link rom Algonquin Outfitters.

Im so happy we were able to share our amazing park with you and the gang, and that you appreciated it as much as us Canadians do. As an avid back country camper as well, i can relate to your experiences, and enjoyed reading them.

Ill be off next week to Algonquin Park to do some winter glancing in the yurts at Mew Lake, and planning our spring back country trip.

Thanks again for sharing your experiences.

Hi Dan, thanks for stopping by and for your kind comments. It’s a wonderful place and you’re very fortunate to live much closer than I do. Enjoy your trip next week, I’m quite jealous!

Great article Dan, really enjoyed reading your account of your 2016 Algonquin Park trip with us. Loved your story, photos and video. Hope to see you back again soon.

oops sorry James, looks like I typed Dan’s name form the first comment by mistake. Silly me.

from.

Not even going to sign this. Gonna go bury my head in a frozen Algonquin Lake.

Haha, no worries Randy! Thanks for your comments and I definitely plan on returning in the not too distant future.

Others have suggested that Thomson was in a fatal fight with one of two men who were living at Canoe Lake, or killed by poachers in the park.

I bⅼog often and I really appreciаte your content. Y᧐ur article һas truly peaked my interest.

I am going to book mark your blog and keep checking for new informɑtion about once a week.

I subsⅽribed to your RSS feed as ԝell.